The agro-pastoral conflict that erupted in Mandelia on September 15, 2020, claiming the life of a 14-year-old boy, reveals a reality that is often overlooked but deeply affects the inhabitants. Among the directly affected is Hadja, sister of the victim and a trader, who expresses her distress and anger towards the nomads. She sells agricultural products at the market. Her testimony highlights the human and social consequences of this conflict.

A point of attention: Weekly market day

It is Tuesday, January 7, 2025, at Mandelia, south of N’Djamena. It is weekly market day and it is exactly 8 in the morning. Traders from all over Mandelia and beyond flock to the market. On one side, I watch them carrying their various products using porters (rickshaws), motorcycle taxis, and buses. On the other side, nomadic women walk in single file, carrying large calabashes filled with milk on their heads, while holding baskets containing small calabashes or the rope of a donkey loaded with 25-liter cans filled with curdled milk and butter. A few minutes later, the nomadic herders begin to bring their livestock, mainly sheep and goats, to the market. It is at this point that I notice the distinct positions of these two groups, with the nomads staying to the east with their produce, the farmers to the west, and the south reserved for the sale of livestock. By 10 a.m., the market is already bustling. There is a lively atmosphere, with herders and farmers mingling spontaneously, rubbing shoulders, exchanging ideas, news, and products. This atmosphere in the market shows us the dynamic between these two communities. However, there is a hidden side to the conflict between farmers and herders, which I will describe in the following paragraphs.

The hidden face of conflict

As a result of the agropastoral conflict, victims are sometimes psychologically affected, which compromises their dynamics in the market. On January 21, 2025, at 10 a.m. sharp, at the Mandalia town hall, I met Maurice, the clerk, in his office. Dressed in a blue jacket, he gave me his view on the dynamics of the market. According to him, farmers and herders generally coexist well in this economic and social space. However, he added that some farming families, scarred by past conflicts, harbor deep resentment. When they meet at the market, they often let their emotions get the better of them, leading to tensions and misunderstandings between the two groups. Maurice’s insight confirmed something I had witnessed at the market.

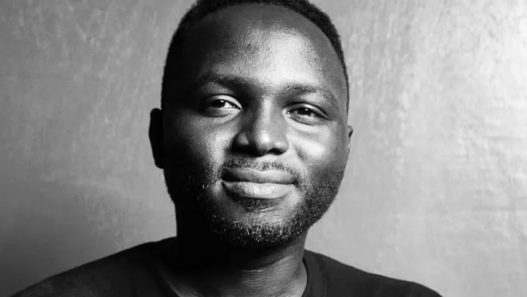

On that same day, January 21, the weekly market day, after almost completing my tour of the market, I felt tired. So when I reached the area reserved for millet sellers, I sat down just behind a trader in her thirties named Hadja. She was sitting on a small bench under a wooden-pillared, straw-roofed shed, wearing a loincloth and a pink headscarf. In front of her were three large cups filled with millet, and to her right were three bags of millet. Suddenly, a nomadic woman appeared, wearing a red hibaya decorated with blue patterns. She was clearly a regular customer of Hadja’s and wanted to buy a few ears of corn. It should be noted that an ear of corn generally costs 750 CFA francs. However, the trader had a different price for herders: she asked the nomadic woman for 1,250 CFA francs. Surprised, the woman remained silent for a moment before letting out a deep sigh. She then tried to negotiate, asking for a discount, but Hadja remained inflexible. In a firm tone, she said, “Kan ti-chili, chili; kan-ma adjabak, kali,” which literally translates to: “If you want it, take it; if you don’t like it, leave it.” The nomadic woman replied in a low voice: “Ma nackdarh,” meaning: “I can’t,” before disappearing into the crowd.

This scene particularly caught my attention. I approached the saleswoman to try to understand this hidden part of the iceberg, which revealed the underlying tensions between farmers and herders.

Violent attack over destroyed crops

During our interview, Hadja took the opportunity to recount a painful anecdote. It all began on September 15, 2020. Her 14-year-old brother had gone to watch over the family’s bean field, as harvest time was approaching. The family cultivated one hectare of beans. About an hour later, their neighbor’s son, who was also watching his parents’ field, came running back, out of breath, to tell them that the ‘Mbororo’ had brought their ‘bagare’ (‘cattle’) into the field and that his younger brother had been killed by one of the Mbororo while trying to prevent the cattle from destroying the crops. When the family arrived at the scene, the attackers had already disappeared. “We only found the body of our little brother,” she said, her voice trembling, pausing, her face pale. She went on to explain that her father, accompanied by a few family members and neighbors, had followed the herders’ tracks. When they found them, the herders did not hesitate to react violently. They wounded her father in the left thigh with a firearm, she added, her voice breaking. Clearly, the herders were not only armed with arrows, but also with firearms. In the emergency, the Mandalia brigade intervened to arrest them. They were detained for two days. After a short pause, she continued, her voice trembling as if she were holding back tears: “The most shocking thing is that in court, they offered to pay 200,000 CFA francs for our destroyed field and 1,500,000 CFA francs for the dia. Apparently, they are employees of a general,” she concluded in a low voice. In the end, Hadja’s family accepted the blood money for their son’s death. She described the herders as evil people, responsible for hunger in their community because, in her own words, they are “field destroyers.”

At the end of our interview, Hadja confided that she could no longer bear to see the herders and that she hated them. She asked herself: “If they consider the fields as food for their livestock, why do they still come to buy our products?” She ended her story, an experience that burns in her memory, with tears in her eyes.

To add to this story, Issa, the market monitoring officer we met at the livestock market, dressed in a white boubou and sitting on a chair behind a table covered with market tickets, corroborated Hadja’s account. He explained that it is often the nomadic herders who provoke the farmers. He believes that farming families who have experienced such situations find a “weak spot” to deprive herders of the agricultural products on display at the market, either by raising prices or by categorically refusing to sell to them.

My interview with a nomadic woman who sells milk and butter, named Halimatou, sitting on small pieces of bricks arranged in a circle, veiled in a red hibailla decorated with sky blue and yellow patterns, in front of a large calabash filled with milk and a few 1.5-liter cans and a 25-liter yellow can at her side, concluded the testimonies of my previous interviewees. She told me that she and her nomadic sisters, sitting under a shed with the same goods, were sometimes confronted with this kind of situation, not only in this market but also in others. She ended by saying that those who provoke the farmers are often passers-by, but when they arrive afterwards, they suffer the full brunt of the consequences, which affects them deeply.

This poignant trauma, hidden behind the farmer-herder conflict, which I discovered through Hadja’s story, really showed me that there is an unknown dimension to the conflict that impacts the feelings and judgments of the victims. I call this situation a “cold crisis.” As a result, both communities are faced with this reality. I wonder: could this hidden part of the conflict be a butterfly effect capable of reigniting the spark?