I am usually not defining myself in terms of my family, my ethnic group, nor my religion. I prefer to define myself simply as Chadian, an identity that I feel brings people together.

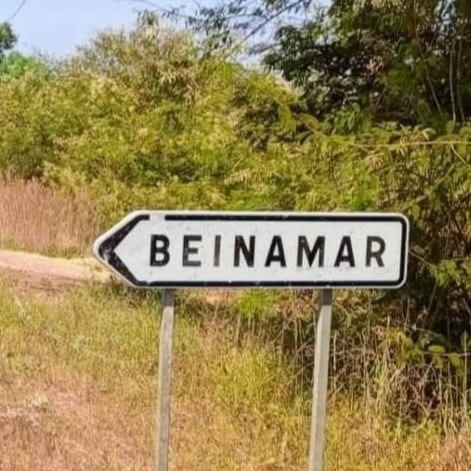

I was born and raised in Beinamar in southern Chad. My father, one of the first intellectuals in the region, is now deceased and is buried in the family courtyard in the “A” neighborhood. As a child I spoke fluent Fulani and Gorane, two languages I still have some knowledge of today, as I grew up with these two Muslim communities.

The Kilangs are Ngambayes from western Logone and western Mayo-Kebbi who differ from other Ngambayes in their speech, with slightly different intonations and a few words that are unique to them. They live mainly from agriculture and small-scale livestock farming.

I still remember as a small child seeing images of Gorane people being repatriated from Cameroon in large trucks. They were settled in Beinamar, a town on the border with Cameroon. The mayor of the town at the time, Mr. Deounaye Nguissibé, who was also my adoptive father, allocated them land to settle on, including a large plot belonging to my family.

My eldest sister had a daughter with Rachidou, my classmate and friend of Peulh origin. My niece Maïmouna, raised as a Muslim, was married a year ago according to Muslim traditions.

It was in Beinamar that I started playing soccer and went to school for the first time. We lived there in peace alongside the Goranes, the Peuls, and the Mbororos. I still talk to most of my Goran childhood friends almost every day. Some of them proudly bear their #Ngambaye nicknames. Whenever I visit my mother, who still lives there, she calls my Muslim friends to come and eat at our family home.

One day, when I was very young, soldiers from Moundou or N’Djamena raided our home in the middle of the night to arrest militants from the URD, an opposition political party created by Kamougué. My older brother Jean-Claude managed to escape and take refuge in Cameroon. The others, less fortunate, were arrested and taken out of the city and executed. That was my first childhood trauma. Among them were uncles and cousins. When I asked my mother what they had done to deserve such a fate, she simply replied: “They were opponents.”

As an isolated area in southern Chad, Beinamar is a breeding ground for abuse and injustice, where intelligence agents and the authorities make their own laws. Yet it is also a fertile region, one of the breadbaskets of western Logone.

Having grown up in this part of the country, where indigenous people and other Chadians have lived together peacefully for years, I can say without hesitation that the real problem in this village is its administrative authorities.

When opposition leader Succès Masra was arrested and accused of being behind the tragic events in Mandakao, a few kilometers from Beinamar, I called my cousins in the village. Their response was unequivocal: “Who in Mandakao knows Masra?”

The state has the means to crack down on any political actor. But exploiting ethnic and religious divisions to divide the Chadian people remains the worst thing that could happen to us.