In a national context marked by tensions between herders and farmers, the village of Kole in Southern Chad, is an exception. Located in an agro-pastoral area, this village demonstrates that it is possible to live together thanks to the adoption of field cultivation by herders. Our meeting with Fulani chief Oumar Ali Paul of Kole, tells a story of coexistence between the two groups. His double first name – Muslim and Christian – symbolises the richness of a coexistence that rejects religious and cultural barriers.

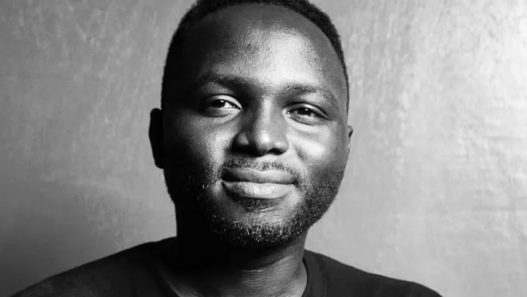

An encounter with Oumar Paul Ali

We call our host on the phone. A few kilometres later, we receive his incoming call, like a guide keeping us on track through the thick vegetation. The road passes villages of round, thatched huts. Children run up, barefoot, raising their hands in greeting.

At our arrival a welcoming committee awaits us under a large tree. Colourful rugs are already spread out on the ground. We are invited to sit down. Greetings fly back and forth, punctuated by smiles and welcoming gestures. In keeping with the tradition of hospitality, cups of milk are passed from hand to hand. “Try it, it’s milk from our cows, pure and sweet,” says one man. Between sips, conversation begins, laying the foundations for a friendly discussion. Then Oumar Ali Paul, the head of the house, takes the floor. His story immerses us in the intimacy of his personal story and that of the community, a way of life and a successful venture on cohabitation.

Kole is located between Makene and Koutoukouman, where sorghum and maize fields stretch to the horizon. Surrounded by influential members of the community Paul starts the story: “Before, we used to graze our animals and then return to the riverbank. But the chief of the Baïkoro canton gave us this place.” The chief said, Paul continues, that these Fulani are our brothers and that they should live with us. “Since then, we have been farming the land and raising our animals here,” he continues.

Finding common ground

In this agro-pastoral community, land is at the heart of trade. “Sometimes we rent farmland from the indigenous people. The price is 10,000 CFA francs. If you can afford it, you can rent 5 to 10 fields. When it’s time to plough, the Ngambayes arrive with their oxen to work in the fields. When it’s time to harrow or plough, my children and I work. But we also call on outside labour,” explains Paul. The price is discussed in advance and once it is accepted, the work is done. It’s a tradition that continues every year. “That’s our strength: working together,” says Paul in a peaceful tone.

Living together is not without problems. Sometimes the fields are devastated by animals. But Oumar Paul smiles: “No man is perfect. Tongues and teeth tear each other apart, but they are condemned to live together. When a field is destroyed, the farmer identifies the owner of the cattle and tells him about the damage. The two find common ground. If they cannot reach an agreement, the matter is referred to the community mediation committee. And if the problem persists, the village chief decides. But in 38 years of cohabitation, no conflict has ever ended up in court.”

As a lesson in humility and conflict prevention, awareness-raising work is carried out every year. “In July, we encourage livestock farmers to keep their herds in enclosures until January. This protects the fields. After the harvest, the animals are let out to graze on the sorghum and maize stalks,” says Paul. Mutual aid goes even beyond the fields. Farmers sometimes lend money to crop growers to start their sowing, and the latter repay them after the harvest. It is a circular economy of solidarity.

The name Paul, a history of cohabitation

Behind the name ‘Paul’ lies a unique story. “The name Paul doesn’t come from my family,” Paul says while laughing. He recounts: “My mother, full term pregnant, was returning from Moundou, where she had gone to sell milk. On the way, she was caught in a torrential downpour. She took refuge at the home of a fisherman, Paul Ngourmian. That day, she gave birth to me at his house. The next day, my father came to fetch us, bringing a rooster and 250 CFA francs, a large sum at the time,” Paul laughs, “to thank the man who had taken in his wife and child.”

Around us, the huts and enclosures bear witness to an organised community life. Children’s laughter echoes, women husk millet, and Paul calmly and humorously continues his story: “That’s when Paul gave me his first name. He said to my father: “When this child is 7 or 8 years old, bring him back and I’ll enroll him in school.” But before that age, my father sent me to tend the oxen.”

In Chad, giving a child a name is not an ordinary decision. It is a meaningful act, a mark that will follow the person throughout their life. It is rare for a name to cross religious community boundaries. Yet this is the case for Oumar Ali Paul. Born into a Muslim family, he has a Christian first name. This is unusual in a country where a person’s first name is often the first sign of their religious or cultural affiliation.

“When this man said that the child would bear his name, no one in my family objected,” says Oumar Ali Paul with a smile. This choice, accepted without resistance, is indicative of a time when the question of whether one was Christian or Muslim had no place in life decisions.

And so it was that this seemingly simple name became the seal of a story. “The name Paul is a special mark on my personality,” he says. It is a story that connects people.

Kole stands for ‘trust’

The village of Kole once fell under the name of the village Makena, but was renamed Kole, or holare in Foulate, meaning ‘trust’. Translated into a saying it means: “I do not fear you, you do not fear me”. Multiple groups in the village come together and hold meetings in which they give advice to their children on peaceful cohabitation, on living together. In Pauls’ words this means that the citizens understand that Kole or holare is not just a name, but a collective commitment.