ارتفاع وانخفاض للقرية العجيبة

“A jagal amin ragarewal ha Dourbali, minnani hubaru diyam worti ha Cilcilce… The last time we went to Dourbaly, we heard the news that ground water in Cilcile emerged,” says Bint asheikh. She is of the Maare Fulani clan and the one and only daughter of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq, which has earned her the nickname bint asheikh (the daughter of the Sheikh). She gloats as she relates the story. When she smiles with her dark accentuated lips closed, you can still sense her youthful mischief. Bint asheikh continues: “‘They [the inhabitants of Dourbaly] said: ‘water rose up on the land where your father Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq used to be.’ When we heard the news, we asked our driver to bring us to Cilcile, so that we could see the water of our father. A herder with a walking stick in his hand had stopped there, stomped the ground, and water squirted. Thereafter, people started going to the spring, carrying, drinking, and washing their faces with the water. Among them were the blind, when they washed their faces, their eyes opened. Among them were the ill, whose drinking suddenly healed them. Among them were the paralyzed, who upon drinking and bathing in the water could move. The people in Dourbaly said: ‘We drank from it and we benefited from it.’”

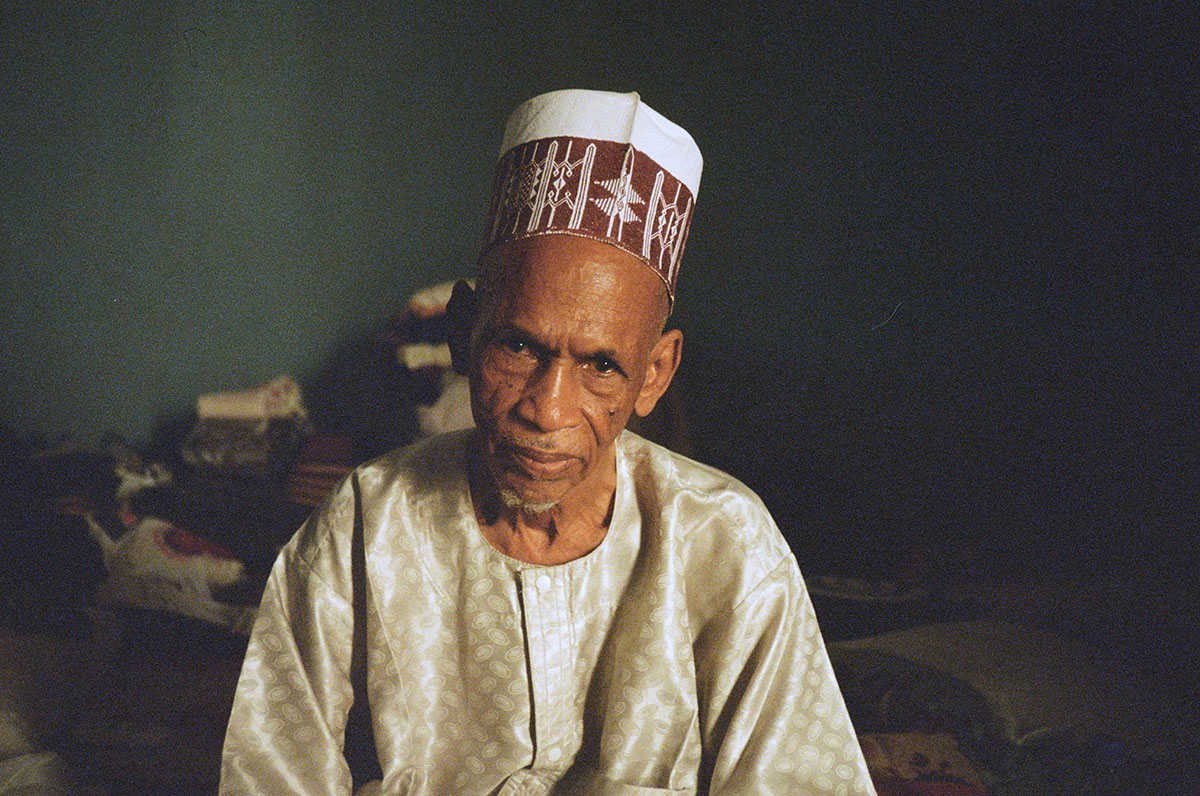

Bint asheikh relates the story sitting in her dark room that is decorated by a glittery pink curtain and dozens of posters of famous Tijani Sheikhs from Nigeria, Senegal, and Cameroon. The room is inside the zawya (meaning, a combined Quran school and mosque). Her father constructed the space in the heart of N’Djaména in 1973. Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq was a religious leader, scholar, herder, and farmer who has roots in Cameroun and Nigeria. He was a follower of the Senegalese scholar Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse and a prominent student of Sheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih al-Yarawi in federal Nigeria. In his turn, Sheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih was a student of Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse. Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq was a key player in spreading the Tijani order in Chad. He was one of nine sheikhs to whom Sheikh Ahmad Abu al-Fatih sent a letter, granting them absolute authority over the affairs of the religious order in Chad. Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq passed away in 2001, but he has left an ineffaceable mark on a Fulani and Tijani community that finds itself North, East, South, and West of N’Djaména. Communities from Chad to Cameroon and from Nigeria to Senegal know of his deeds and name and believe in the supernatural interference of the Sheikh in the human world. Like Dourbaly’s inhabitants, who taste, feel, and see the water of the magic well that supposedly has healing qualities. The sensory engagement reflects a worldview of a Fulani community in awe and the continued religious significance of the Sheikh. There is more to the miracle. It brings to attention the object of desire, healing water, in a community that has faced health hazards and water shortages since at least the 1950s.

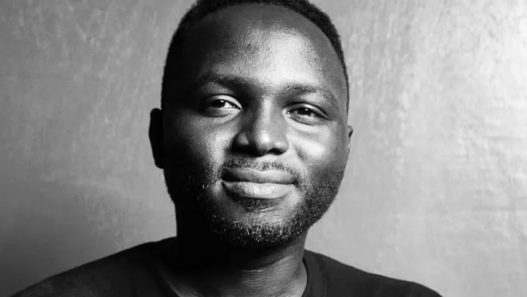

The authors of this article are Said Aboubakar and Luca Bruls, who met each other around the zawya in the tight streets of Chad’s capital N’Djaména. On a late night walk to the bus, Said expressed his wish to write the life story of the Sheikh and the idea came upon us to collaborate. Not long after, we began our search for what turned out to be much more than the account of a man with Islamic credentials. It uncovered the story of a partially urbanized and sedentarized group of Fulani nomads. Due to new living conditions, as well as the poverty they faced, they adapted their social organization and sought for financial stability through agriculture and what N’Djaména had to offer. Young men did business on the market, while women occasionally sold food and objects within households. The knowledgeable Sheikh played a powerful role in these changes. The more he travelled around for Islamic knowledge and the more Quran schools he constructed, the more he became a man with a large social network and considerable power in his community. Family members followed him in his travels and used his guidance to grow out to spiritual leaders themselves. Pastors’ kids came to study in the city, often leaving their future cattle all together. The Sheikh’s biography and the experiences told by his family members show the importance of Islam in a nomadic group adapting to other lifestyles.

We toured the urban zones of N’Djaména, frequenting the various neighbourhoods where a melange of born city dwellers and former herders had settled and memorized the twentieth century’s happenings. We bumped our way to Hadjer Lamis, where the rain coloured the fields green and farmers and families with little left of their troops of red cows welcomed us in their moss bricked houses. We crossed the river in Chari Baguirmi, the stretched out fields showing the remains of corn and wheat cultivated by Fulani farmers. As if collecting the golden grains between the sand, bit by bit women like Bint asheikh and Zahra and men like Khalifa (d. 2025) and Modibo, whom we meet later, related their lively memories. They rarely seized to mention the place name Cilcile. In order to arrive there, Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq faced East…

The migration that brought fame

The Sheikh’s journey began in Walooji, present-day Cameroon, where he was born, raised and set his goals. Fulani have migrated for centuries, in search for the appropriate environment for their livestock and sometimes for security reasons, as is the case with the family of Sheikh Mahamat Azraq. Firstly, this nomadic family entered Chad because the authorities in Cameroon pressured them to pay taxes for their livestock. Secondly, they sought security from robbery and murder. According to a story of one of Sheikh’s servants, Sa’ina, one day a group of supposedly ‘black Frenchmen with Senegalese origins’ killed the Sheikh’s brother. The comment left us wondering what interactions might have preceded this conflict between a herder and the colonial administration. An event that left many disturbed. These conditions made the Sheikh and his family consider to leave the colonized territories. When Sheikh and some brothers heard about the news of the lands around Dourbaly in Chad, they did not hesitate any longer to leave Walooji. Several brothers and their cows had already migrated to Dourbaly around 1947 and they informed the Sheikh’s brothers about the better conditions in Dourbaly, where they did not face theft, taxation, and shedding of innocent blood, as the story of Sa’ina indicates.

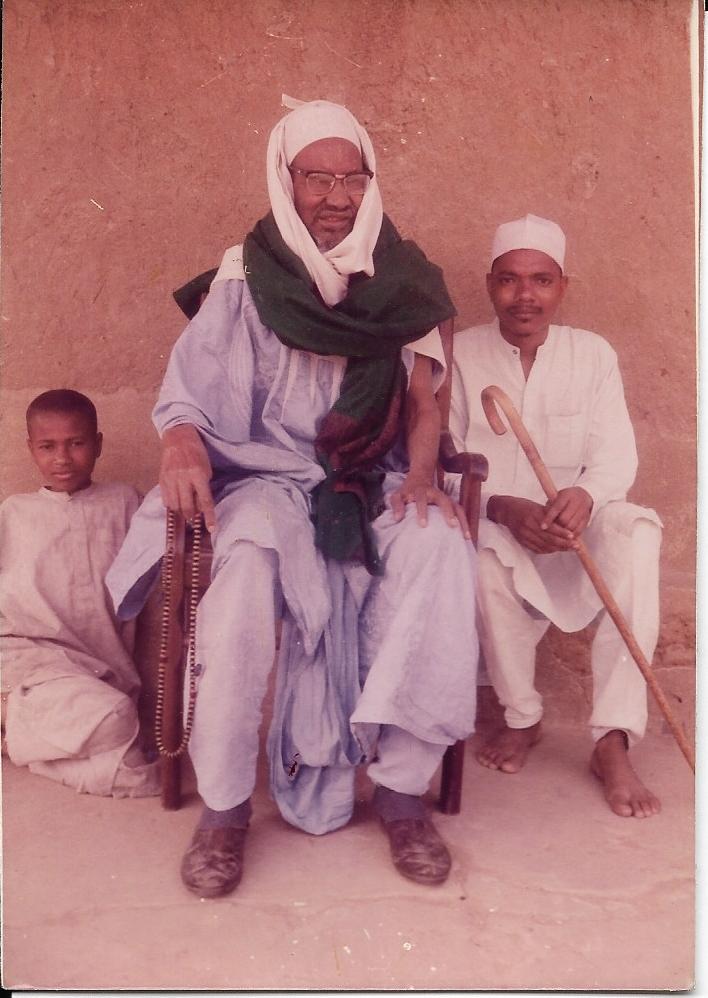

On an early morning in October, we enter the zawya in N’Djaména to do an interview with Khalifa, a cousin of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq. We find a large group of muhajireen, some rinsing and writing their loha (tableau), others washing their clothes. Their master sits in front of them and performs his teaching roles. When we enter the Sheikh’s salon, we find Khalifa and he invites us into the room of the late Sheikh Mahamat Azraq himself. The room is full of souvenir photos of the sheikhs who used to come to visit Sheikh Mahamat Azraq, including images of Nigerian Sheikh Abu al-Fatih and the sons of Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse from Senegal. We sit ourselves on a carpet, facing a closet full of Islamic scholarly works. When Khalifa tells us the story of the journey his uncles and his father made and the hardships they faced during the march, he seems to be moved. His voice rises and falls, especially when Said tells him: “I can’t believe that you have overcome all this,” and Khalifa responded, “Kay” and shakes his head left and right, as a result of his emotion. Khalifa continues: “It was a very difficult migration where we faced hardships. The distance from Walooji to Dourbaly was large, and the sun was so hot that the soil under our feet felt like embers because we were travelling this distance on foot behind the livestock.”

When the Sheikh finished his studies, he joined them. He found them in Derbaji, a village close to Dourbaly. There, he started teaching the holy Quran to young boys and girls. Since religion has a major influence on the Maare Fulani, the community surrendered their affairs to this man full of Islamic wisdom. The relevance of religion in the community partially has to do with the role its Fulani members believe they played in spreading Islam throughout Africa. The family, first of all, trusted Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq’s clerical and spiritual qualities. He was of their flesh and blood, and so people gave him leadership.

From then on, the Sheikh played a role in the movements and travels of Maare Fulani. Not only did people obey him because they saw violating the Sheikh as a violation of the Sharia. He and his brothers also owned a considerable number of livestock, which is an important factor in the geographical organization of Fulani. In 1952, the Sheikh and his relatives moved to Gawil, an area fifty kilometres away from Derbaji. The land there was rich in grass and ponds, and thus a better spot for the cows they bred. In Gawil, the Sheikh opened his first khalwa, where he only taught the children of his brothers and relatives. Just a few years later a new opportunity arose to migrate to Cilcile in 1957, so Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq and some of his relatives moved, while others stayed behind and continued to run the khalwa.

The well is plenty

From the conversations with Bint asheikh and Khalifa about the years the Sheikh and his relatives spent in Cilcile from 1957 to 1978, it became clear that social life in Cilcile continued to be marked by mobility. People and cattle followed the seasonal whims to make ends meet. When the first rain drops fell in autumn, Maare across the country returned to Cilcile’s soil. The in turban shelled herders who had settled in villages like Hedide around Lac Chad slapped their sticks on the bums of their cows, nearing inch by inch. The muhajireen of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq, his older students and their wives in N’Djaména, put few possessions in bags and left for the modest state of the village, wishing for a fertile moment. In this village, herders, city dwellers, and farmers of the Maare Fulani met every year when the soil became soppy. Water is an element essential in life, equally so it is a driver for connection. It brings people together.

On a tiny veranda with a straw roof in the village Meebi on the riverbanks of the Chari, we meet Modibo. Modibo is 77 years old and was born around Lac Chad. After studying the Quran with Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq in N’Djaména, he decided he wanted to do agriculture and moved to Cilcile, where he stayed all year around. He does not regret his days in the village, but elaborates with a sour heart how the village slowly fell apart. In Cilcile people lived near the well Bir Tourné Moussa Nayn, on the land of a Fulani by the name of Beské. To get water from the well, they walked with their donkeys for an hour. Cow-breeding Arabs, under the reign of Sultan Ahmed Gojal, owned the well. The Arabs lived in another village and frequently came to greet their Fulani neighbours. Modibo relates, “Humma kullo jo fi bakanna. Sabab Sheikh Azaraq da… They all came to our place. Due to Sheikh Azaraq.” He tells how they were like family. “It was due to mahabba (affection) and religion.” The curiosity for the Sheikh thus not only stuck with the Maare Fulani, but also with other ethnic communities. During an interview in Mani Kosam, a village in Hadjer Lamis, Hisseini added that the Sheikh had Arabs and Massa students in Cilcile. Hisseini is a man of 85 with enormous glasses and an abundant charisma, who spend his childhood with the Sheikh in Gawil as a herder. He praises the Sheikh and remembers his incredible smell of sandal wood. We listened to his rasping voice among the soundscape of his bleating goats in Mani Kosam. He loved and still loves the man: “Sheikh was a fukaraku (poor man). But the elders loved the man, because he was a modibo (religious scholar) who knew how to read.” Despite his poverty, Sheikh gained status for himself and his community.

Sheikh undoubtedly imposed Islam wherever he settled. When the Sheikh and his two wives arrived in Cilcile, he taught the children of his brothers and sisters around a fireplace, a habit Sheikh’s descendants in Meebi have held on to. One of his early students, whom like Modibo lives in Meebi, took over the classes in Cilcile when Sheikh left for N’Djaména in the late 50s. The Sheikh became more and more integrated in the urban zones of N’Djaména. Although life was not easy in the poor districts of central N’Djaména, he managed to get by as he gained a bigger Muslim following. Meanwhile, his students in Cilcile sedentarized and became teachers of the Quran. Their means of income changed. Modibo and three others were responsible to cultivate cereals and to read the Quran at night. Their wives focused on the processing of the grains. During the rainy season, they welcomed their cow-breeding relatives and Sheikh’s muhajireen from N’Djaména. The expansion of Islam among Maare Fulani was a driver to adopt an agricultural lifestyle. Because of the rising demand for food crops in the city due to a growing number of students in the 60s, Maare Fulani turned to cultivate food crops to meet the demand.

To this day, on the other side of the road of the zawya lives Zahra. Zahra is 69 years old. Zahra’s lafay hangs loosely over her head. Her long slender hands, characteristic for the tall female herders, touch Luca’s legs as she offers us her perspective on the agricultural activities in Cilcile. In 1968 the newly wed Zahra, a herder daughter, settled in N’Djaména at the age of 12. That same year, she travelled with her husband, another couple, and a half of Sheikh’s muhajireen to Cilcile. Every year, during a period of five years she stayed in Cilcile for six months. She honestly says the days were not easy, together with other women she carried out khidma murr (hard work). Her words carry us away: “Amshi al-mi, yimshi khatab. Niduggu khala bi ideena, nisayyu eish. Da shughl hana ajur bass… Walking to get water, wood. We grained wheat with our hands, we made boule. It was work for ajur.” An Islamic motivation that also echoed in Bint Asheikh’s words: “Agriculture has baraka.” Zahra went to Cilcile because the Sheikh asked her to and she would not refuse a request from him whom she lovingly calls her father. So in the late 60s and early 70s, women in the village prepared food, around 300 students planted grains of wheat, corn, and okra, and harvested when the stalks glistered in the Sahelian sunlight. The moment the rich rains were over, they cleaned out the lands and one responsible man brought half of the yield to N’Djaména. There, the wives and cousins of Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq stored the 30-40 bags inside the zawya, sufficing the Quran students and Maare families in the zawya of food nearly all year around.

Farewell: Changing direction

But the stock did not last. Fatigue thickened in Cilcile. After Zahra left Cilcile, her aunt, one of Sheikh’s wives, moved to Cilcile but died of a severe decease she contracted from the waters. Those left in the village faced increasing water shortages from 1974 to 1978. Many people resorted to eating leaves to cover their hunger. Modibo in Meebi said with a sad face: “Bir da wigif bass, akl ma fi, al-mi ma fi… The well emptied out, there was no food, no water. That has brought us here.” The herders stopped coming with their cows in the rainy season. At the start of the dry season of 1978 the sedentarized group of men, women, children, and cows left Cilcile for good. As soon as the Fulani had arrived, as quick they left by foot in search of new livelihoods and greener pastures. Some went to Hadjer Lamis, others to Meebi, and again others to N’Djaména. Hausa arrived on the soil of Cilcile, not long after the Fulani left. They installed several water pumps and started a weekly market.

Around those years, family members also lost most of their livestock due to worms. The necessity to buy food made some sell their cows. They, as well, altered their routes and future plans. Some settled in agricultural villages, others sought jobs in the city. The zawya in N’Djaména, however, was and continues to be a central hub where Maare Fulani meet and exchange information. Islam is an important carrier among the Maare, of whom many have changed a herder life for the city and of whom the majority cannot only live of the profits of cattle herding. Flexibility and changeability are indispensable parts of the Sahelian landscape and its inhabitants.

Persistent water scarcity

Sheikh Mahamat Azaraq was able to establish a large religious institution despite the hardships he faced from early on. He brought people together, be they in the village or the city, the khalwa or the grazing fields. He played a role as a brother, father, and teacher in connecting members of the Maare Fulani. Moreover, he was an advisor and spiritual guide during the economically and politically difficult circumstances the Maare Fulani faced, as well as the ecologically harsh environments they lived in. As rural dwellers, they sought refuge with their livestock at ponds, basins, and reservoirs. With the years, drought led to the cessation of agricultural production that fed hundreds of people in Cilcile and N’Djaména. Up until now, a source as wealthy as Cilcile has not been restituted among this family. With the pressure of climate change, the water cycles in the Sahel change and Fulani adjust their routes accordingly. This results in a continued exchange between the city, the herder, and the farmer.