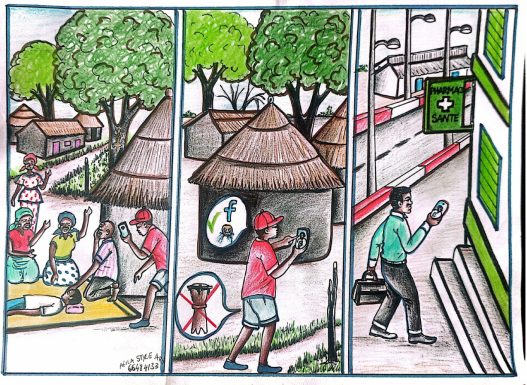

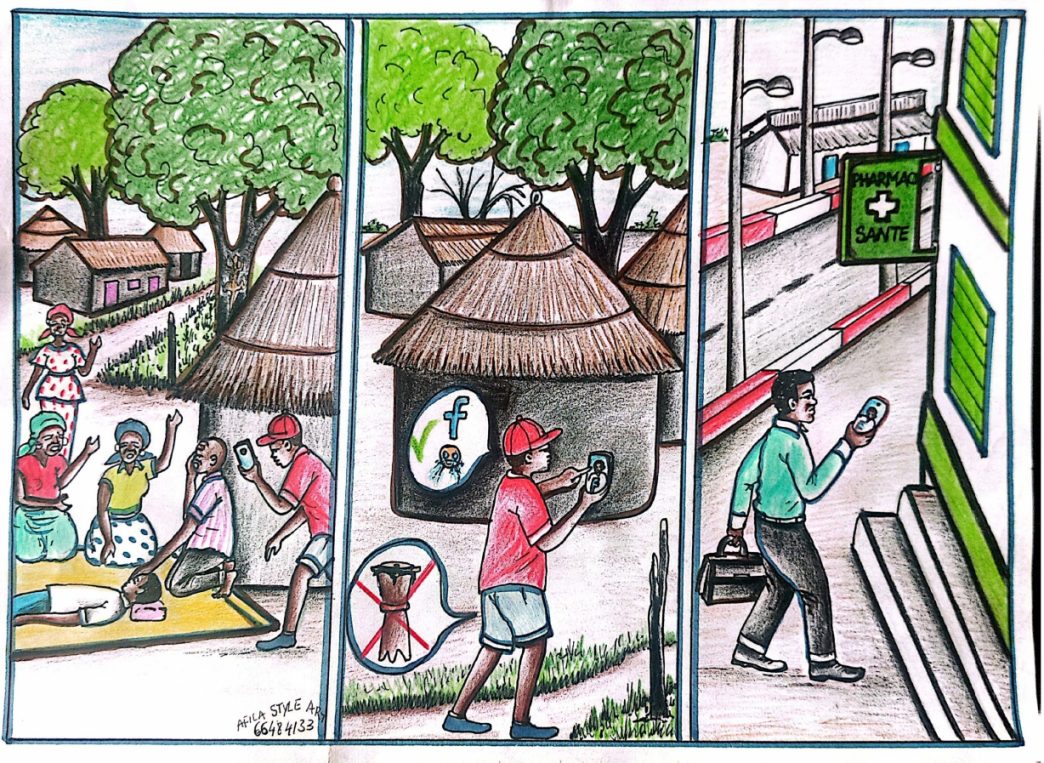

Illustrations: Bénaïdara Delezer

In the early hours of October 31st, the people of the Atrone neighborhood in the 7th district of N’Djamena woke up to horror. A simple, seemingly insignificant short circuit was enough to start a deadly fire. In a matter of minutes, flames engulfed a house, killing an entire family: a father, mother, and their two children, a boy and a girl. The silence of dawn was broken by screams, smoke, and a sense of helplessness. “We tried everything to save them, but it was already too late,” told a neighbor, still in shock, to the online newspaper NdjamPost.

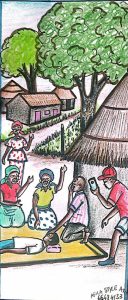

While the family was still asleep, unaware of the tragedy that had just struck their loved ones, the news was already taking on another form: that of viral content. As if by mechanical, almost automatic effect, social media went into overdrive. Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, online media, personal accounts: posts exploded from all sides. Photos of the burned-down house, unbearable images, hasty comments. Unfiltered. Without respect for the people mourning. “I learned about the tragedy on Facebook, from France, like everyone else. At first, I didn’t believe it, because no one in the family had called me. They were looking for the right words to tell me. I was completely overwhelmed when I saw the images circulating on social media,” said the eldest member of the family, her voice thick with emotion at the funeral.

The shock of public mourning

In the age of social media mourning, already a heavy burden to bear, becomes a double punishment: that of loss and that of exposure. Families have neither the time to mourn in silence nor the space to prepare themselves psychologically for the announcement. Death is no longer announced with humanity; it is consumed as information, shared, commented on, and sometimes even ‘liked’. This practice has become a trend on social media.

Whether it’s a family member or a simple internet user, everyone feels entitled to post without asking the consent of loved ones and without considering the profound psychological consequences of their actions. At a time when everything is shared in real time, a question arises: how far will we go in the name of information? Is society suffering from the excesses of social media?

Tar-Asnang’s perspective on the use of social media

On the porch of his house, Tar-Asnang le Dotangar, a retired teacher and linguist by training, slowly turns the pages of a book in English. Attached to tradition, he attaches great importance to books. “I read a lot,” he says. “My main source of information is books, followed by the radio, which I listen to at specific times, especially for health programs.” He remains cautious about social media. He only stops to read articles whose headlines catch his attention: “I read quickly, I don’t linger.” But he remains convinced: “Much of what is published is not true.”

Tar-Asnang highlights the many risks associated with digital information: health risks, manipulation, scams, and misinformation. According to him, young people, attracted by the exponential speed of digital technology, copy what they see on social media to the detriment of ancestral cultural values. ”They are forgetting our customs, our traditions, our way of announcing important events”. To illustrate this, he tells his own story: “I was very young when my mother died. No one told me anything. I didn’t attend the funeral, I don’t even know where she is buried. Even today, I can’t answer my own children’s questions about their grandmother’s grave.”

Death, announced with dignity in the past

He recalls the tradition: “Back in the days, the announcement of a death was never a sudden or improvised act.” It followed a precise ritual, developed through experience and respect for the bereaved families. After a person’s death, several hours would first pass, the time needed to clean the body and perform the first acts of dignity. All this, he says, was done to “preserve the emotional balance of the community.” Tar-Asnang continues: “Only after that was the announcement made, using the tam-tam.” Its characteristic sound conveyed the news and was recognized by everyone in the neighboring villages. It was a simple way to protect the family from sudden shock, a respectful way to accompany their mourning. Today, with social media, everything happens without a filter. “Sometimes we get the news on our phones while we’re on the road or at the market, and the shock is immense,” he says.

A family shock at the Dembé market in N’Djamena

“I have a cousin in N’Djamena who learned of her father’s death while she was at the Dembé market,” says Tar-asnang. ”It was when she logged on to Facebook that she discovered the news. She lost her balance, the shock was so great, and the people around her did not understand what was happening to her”. For Tar-asnang, this is proof that social media can inflict invisible wounds where tradition sought above all to spare people’s feelings.

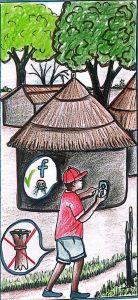

Between Tar-asnang’s caution and the evolution of social media, a debate is emerging: how can tradition and modernity be reconciled? Social media has revolutionized the way we obtain information, sometimes at the expense of human sensibilities. But they also offer opportunities for learning, employment, and communication. At the heart of this intergenerational dialogue, one conviction emerges: neither rejection nor blind acceptance

Sem Alim, a young notary, has established himself as one of the moderate and thoughtful voices on the issue of social media use in Chad. It is not a question of condemning social media, but of learning to use it responsibly and consciously in his opinion. Digital technology can be a tremendous tool if we learn how to use it he says: “Today’s young people have a powerful tool in their hands. They must take advantage of it to grow and rise to the same level as other young people around the world,” he emphasizes. However, Sem Alim notes that many young people use social media not to learn or educate themselves, but to spread hate speech, personal attacks, or propaganda that does nothing to contribute to their development.

Strengthening the role of the state and civil society

For Sem Alim, the solution lies in education and critical thinking about digital technologies: “The state and civil society must invest in teaching young people how to use social media responsibly,” he says. He proposes relying more on associations and community initiatives to raise awareness, educate, and guide young people toward constructive use of these platforms. In addition, he believes that an appropriate regulatory mechanism must be put in place to prevent abuse.

The challenge is not to shy away from social media, but to use it intelligently so that it becomes a lever for personal and collective development. “Today, as soon as a death is announced, some people post photos without permission, solely to attract likes and comments.” This is foreign to Ngambaye culture (one of the many ethnic groups in Tchad) and must stop, he believes.

On the political front, Sem Alim points to a culture of conflict that fuels hate speech online. Young people have come to believe that politics is about insulting, humiliating, or demonizing one’s opponent. “A political opponent is not an enemy. Even within the same family, brothers and sisters may belong to different parties and defend divergent ideologies. That does not justify hatred,” he explains. He therefore calls on the state and political parties to take responsibility for educating their members and promoting political debate based on ideas rather than personal attacks.

At a time when social media plays an important role in the daily lives of young people in Chad, it is essential to rethink its use. Hate speech, misinformation, political conflicts, and the loss of cultural values show how fragile digital technologies can become when there is a lack of accountability. However, social media is neither a danger in itself nor a miracle solution. As Mr. Sem points out: “It is not a question of rejecting these tools or adopting them blindly, but of learning to use them wisely.” The important thing is to create a space for education, constructive dialogue, creativity, and fulfillment rather than a breeding ground for division.

The responsibility lies with everyone: the state, which must provide guidance and education; political parties, which must train their followers; associations, which must raise awareness; and above all, young people themselves, who must use digital tools in a civic and constructive manner. It is in this capacity that social media will become instruments of progress capable of contributing to the development of young people and the growth of the country. Chad deserves a space that helps build a stronger, more united, and forward-looking society.