A seasonal adventure that depends on water and rice cultivation: that is the migration of young people from Gao to Algeria. Coming from a region located along the Niger River, the young people of Gao engage in agricultural activities, specifically rice cultivation. This is a traditional crop that depends on river flooding and rainwater. Since river flooding and rain in this region occur periodically, young people establish an annual seasonal schedule: part of the year is spent growing rice during the rainy season and river flooding, and the other part is spent migrating to Algeria.

Firstly, young people in Gao who have dropped out of school or failed at school turn to the farming of rice. They tend their fields while waiting for the first rains, which usually fall in July. Once the first rains have fallen, they sow the rice, hoping that a second, third, and fourth rain showers will follow to help the rice grow in the three months coming. The rains are enough to grow the rice and allow the river to ripen it. Because the end of the rainy season precedes the flooding of the river, the river rises from September to December and begins to recede in January. It is during these months that they harvest the rice and store it in warehouses afterwards. Some of it is used to feed the family, some is set aside as seed for the next crop, and part is sold to meet financial needs and pay for transportation to Algeria.

Secondly, the rice harvest gives way to departure for Algeria. The second half of the year is spent on Algerian plantations. Young people who have nothing left to do after the rice harvest arrive illegally in Algeria. They find employment in various sectors, but most of them are employed on Algerian plantations where, in addition to their wages, they enjoy what they consider to be luxurious accommodation and free meals. This is where they work from January to June. They save part of their wages and send part of them back to support their families left behind in Gao. They only return in June to resume farming activities in July. According to one migrant interviewed: “We cultivate, we harvest, and we leave for Algeria to work until the next season.”

In short, young people from the traditionally agricultural Songhoy community still live off their old agricultural system based on rainwater and the Niger River, as well as their seasonal adventure in Algeria. They have a strategic annual schedule based on rice cultivation and employment on Algerian plantations. This is a survival strategy adopted to overcome hunger and provide for their families’ daily needs. This is all the more important given that Gao, and Mali as a whole, is experiencing a food crisis caused by the multidimensional crisis of 2012. What if the Algerian and Malian governments maintain bilateral relations on the issue of borders?

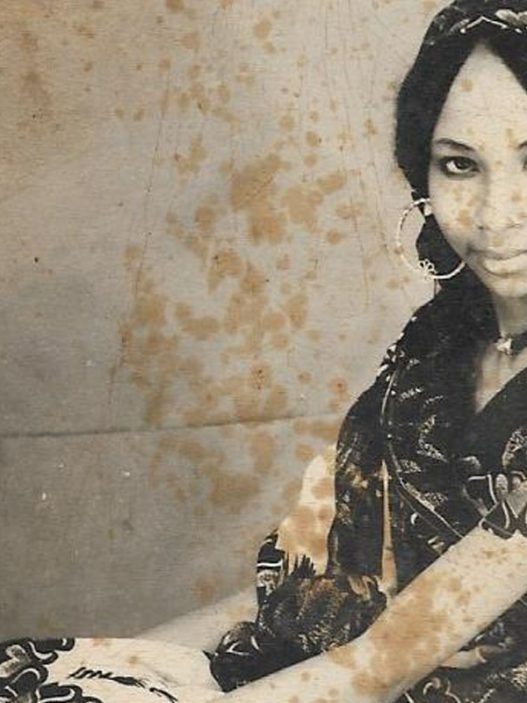

Housing for illegal migrants employed as gardeners and field workers

So is it a right or a motivation? That is the question we ask ourselves. Sub-Saharan Africans who migrate to Algeria in search of employment are largely employed in gardens and fields in southern Algeria. Since agricultural activities are carried out outside the city, the owners of the fields who employ illegal migrants build accommodation in these fields. This is where they house their employees and keep them for agricultural activities such as plant maintenance, watering plants, picking fruit, and caring for dairy cows. A medium-sized building with air-conditioned rooms, a kitchen and modern toilets is made available to migrant employees. The employees are delighted with these living conditions because they have never known anything better; most Malian migrants who make their way to Algeria come from rural areas where they live in mud-brick houses. HG, a Malian migrant interviewed via WhatsApp by the Water Mobility team, admits: “In Algeria we are well housed and well fed. We live in air-conditioned houses, and we eat roasted chicken. We don’t have that in Mali. And when we return to Mali, we see that there is a difference between us and the parents we meet again, which is evident from our bodies.”

These better living conditions are an excellent way to attract illegal sub-Saharan migrants to opt for farm work, given the great need for employment in the agricultural sector in Algeria. As a result, employees stay for years without returning, because it is already a luxury compared to what they experienced in Mali. OS adds: “I spent four years without returning. I worked for the same employer and when I wanted to leave, he asked me to find a replacement, a brother or someone I know well.”

Whether a right or a motivation, the accommodation provided by the employers is also a necessity for illegal migrant workers who cannot move around freely and find it difficult to find accommodation in the city because they are regularly chased away by the Algerian police. Therefore, staying hidden in gardens is a strategy for them to work in Algeria for a long time.

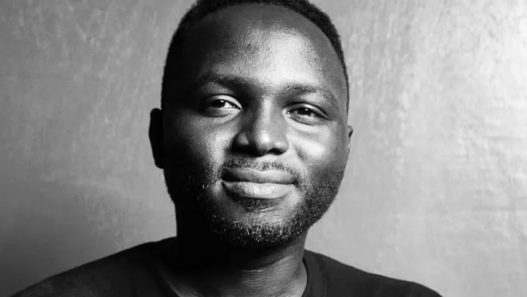

Water Mobility is a project of Voice4Thought (Mali), Bureau d’étude ECA (Algeria) and IHE Delft (the Netherlands) about the mobility of humans due to water-related issues caused by climate change. The project is led by a team made of Algerians and Malians researchers.