The livestock trade in the heart of N’Djamena

Nomadic herders and semi-urban traders from northern and central Chad have settled in the capital to sell sheep and goats. Particularly visible in the 7th arrondissement—mainly populated by residents from the south—and in the 10th arrondissement, on the northern outskirts of the city, these pastoralists occupy sidewalks, public spaces, and even the front of houses to wait for customers. This ancestral activity, which has moved into urban areas, is causing growing tensions between nomads and city dwellers. This article explores this complex reality, between economic necessity and neighborhood conflicts.

On December 23, around 5 p.m., N’Djamena comes alive with pre-holiday excitement. In the neighborhoods of Chagoua, Habena, Amtoukoui, Atrone, and Gassi, hundreds of cattle crowd along the streets. As I was returning home around 7 p.m. an unusual sight caught my attention: a man in his fifties and his teenage son, accompanied by a dusty herd, had just invaded the front yard of a private home in the Atrone neighborhood.

The language barrier, an obstacle to transactions

Returning to the scene the next morning, I decided to play the role of buyer. The customary greetings in Chadian Arabic (“Salamalek abba” / “Maleksalam houlédi”) initiated a cordial exchange. The arrival of a French-speaking customer on a motorcycle suddenly created a comical situation: unable to communicate with the elderly Arabic-speaking herder, I became an improvised interpreter. Finally put off by the prices, the man walks away, not without remarking: “In Maroua, in neighboring Cameroon, there is a specialized market on the outskirts. Why not here, when N’Djamena wants to be the showcase of Africa?” The farmer then tells me his story: “I’ve been coming here for Ramadan and Tabaski since the 1990s. After losing my livestock, I switched to this trade. My son now accompanies me—it’s our livelihood.”

Nan-Toi-Allah, a motorcycle taxi driver, recounts bitterly: “A sheep almost caused me to crash near the old Santana Hotel! The herders are turning the roads into a cattle park. The city council turns a blind eye, preferring to collect taxes rather than regulate.”

A shop manager complains: “Since December 20, their presence in front of my shop has been driving away customers. The smells, the dust, the animals under the tables… And yet we pay our municipal taxes!”

A few meters away, Souleymane, a mobile agent, rails against the stray animals: “Customers have to walk around them to get to my stall.”

Urban grazing remains a bone of contention in N’Djamena. A symbol of a rural economy that is becoming urbanized, it crystallizes tensions between tradition and modernity. In the absence of dedicated infrastructure, this forced coexistence will continue to inflame relations between communities.

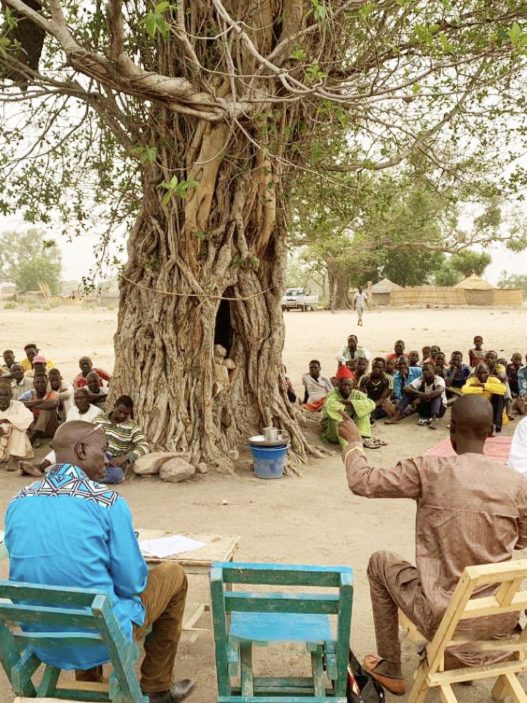

Nomadic pastoralism

This article was written as part of the project “Support for the drafting of reports on nomadic pastoralism by GIZ and Voice4Thought (V4T)” which aims to strengthen social cohesion and reduce polarisation in Chad, particularly in pastoral areas where violence is frequent. For several years, Chad has been marked by recurring conflicts between herders and farmers, which have had a profound impact on the social cohesion of the communities concerned. According to a report by the Crisis Group, between 2021 and 2024, more than 1,230 people were killed and more than 2,200 injured in various agro-pastoral clashes in the south and center of the country[1]. Rural populations are particularly vulnerable to this insecurity. These conflicts often take on an ethnic and religious dimension, exacerbated by political rivalries that fuel community divisions. Social and emotional polarization is very often reinforced by the spread of discourse on social media. Despite measures taken by the government to prevent this violence, the risk of atrocities remains high, threatening the ties between herders and farmers.

The project trains journalists to produce depolarizing stories to counter often sensationalist and inaccurate “bad buzz.” The articles written by participants after their investigations in Mao, N’Djamena, Pala, Chari-Baguirmi, and Doba highlight positive and inclusive alternatives to combat these phenomena.

[1] Crisis Group Africa Briefing No. 199, Nairobi/Brussels, August 23, 2024.