In Chad, polarization is a tangible reality. It manifests itself through divisions between north and south, Muslims and Christians, men and women, among others. However, there are places, such as slaughterhouses, where people come together beyond their affiliations to obtain meat. These spaces, marked by multiple interactions, are not without tension, but they can serve as a melting pot for building a peaceful coexistence in Chad. This is the case at the Walia slaughterhouse, located in the ninth district of N’Djamena.

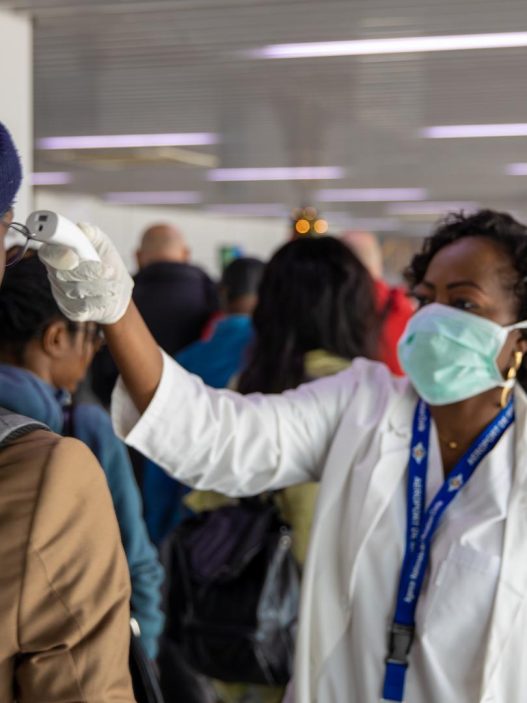

It is exactly 6 a.m. when I arrive at the Walia slaughterhouse, located on the banks of the Chari River. In the cool morning air, I see a crowd of men and women from all walks of life gathered around the meat stalls. All around, garbage and blood litter the ground, accompanied by foul odors. It is in this environment that the butchers carry out their daily work. In the distance, I can see several groups of butchers, both men and women, wearing boots—Muslims and Christians—working side by side. Some are skinning the animals, others are washing and sorting the meat into categories, while veterinary officers, dressed in white coats, face masks, and boots, carry out their inspections. At the same time, some butchers transport the meat in bags tied to motorcycles to the markets. Other meat is laid out on tables where individuals come to buy supplies.

However, there are many problems at this slaughterhouse. Tensions regularly arise between farmers and butchers, particularly due to difficulties in paying debts. Some butchers, lacking financial resources, buy livestock on credit or with an advance payment and then have difficulty repaying the debt within the agreed time frame. One farmer even had to summon a butcher before the local authorities to resolve a repayment dispute. Despite these tensions, most disputes are settled amicably, as explained by Yika, a butcher wemet during an interview: “We buy the animals on credit, but due to poor sales or the high price set by the farmer, we sometimes have difficulty repaying on time. This leads to disagreements between us and the farmers.” Yika has been doing this job since he was a child.

The history of this establishment, where butchers face such challenges, dates back to the 1980s, during the reign of Hissène Habré, the former president of Chad. During my interview with the president of the butchers’ cooperative Chidé Zen I sought to understand the origins of this slaughterhouse. Chidé Zen explained that in the 1980s his father Mahamat Zen, a man of Gorane origin, would slaughter one or two cows on the ground in the public square to sell them. Over time, he expanded his business and hired workers, but the activity remained informal. “It was after his death in 2008 that my older brother Brahim Zen took over and worked to formalize the slaughterhouse in 2009,” he says.

Today, the establishment brings together butchers from different ethnic groups in Chad, creating a unique cultural mix. Various meat-related activities are carried out there, including the slaughter of cattle, camels, and goats. Chidé Zen emphasizes that relations between butchers and herders are generally strong: “There may be disagreements between a herder and a butcher, but very quickly, the two parties settle their differences amicably. Such cases are very rare.”

A customer-butcher relationship

Beyond the interactions between herders and butchers, there are also complex relationships between butchers and their customers. The butchery business involves a relationship of loyalty between butchers and their customers. As I stand in the slaughterhouse next to the butchers displaying their wares, I observe a scene of negotiation between a butcher and a veiled woman carrying a black handbag who wants to buy tripe. The woman offers 1000 francs, while the butcher asks for 1500 francs. While sharpening his knives, the butcher insists: “Madam, give me 1500 francs and I’ll give you everything, otherwise I’ll give you half.” The woman replies: “I have 1250 francs, if you can give me the whole lot.” The butcher finally agrees: “1250 francs? I hope you have change.” The woman agrees, takes the tripe, and leaves, satisfied.

Later, another customer arrives at the table of a butcher named Ali, who is not there. She asks his neighbors where he is. Although there is meat available everywhere, this customer refuses to go to other butchers, looking for Ali. Intrigued, I approach a butcher to ask him why this woman insists on buying from Ali. He explains, without resentment: “Ali is her regular butcher. She thinks we would charge her more if she bought from us. Every customer here has their own regular merchant.”

Ethnic differences

The Walia slaughterhouse is also the scene of ethnic differences between northern and southern butchers. Although these tensions are generally managed, derogatory terms are sometimes used to refer to members of the other group. For example, northerners use the term “Aigré,” which means “slave” in the Gorane language, although most butchers are unaware of its true meaning. One witness explains that “Aigré” is equivalent to “kirdi” in Arabic, meaning “pagan”. For their part, southerners refer to northerners as “Mbiki”, which means “conch” in patois. Despite these differences, the butchers continue to cooperate, as one witness with a look of desolation on his face points out.

Livestock supply

When asked about livestock supply, Chidé Zen explains that butchers mainly source their animals from Arab herders from Massaguet, located 85 km east of N’Djamena, at the N’Djary market, known as “Souk Bagar”, in the capital’s eighth district. Other sources of supply include Loumia and Guelendeng, two towns south of N’Djamena. Some of the Goran butchers are also herders and work closely with Arab herders.

Current situation

Since its creation, the Walia slaughterhouse has experienced remarkable growth. Today, around 500 head of cattle are slaughtered there every day to meet consumer demand. During major holidays, this number can reach 1,000. The meat is sold in various markets in the capital, including Ngosso, Toukra, and Central, as well as other outlets.

Under the supervision of Chidé Zen, the Walia slaughterhouse continues to operate despite the challenges. It is not only a place of commerce, but also a meeting place for different cultures and traditions. It employs more than 100 butchers and seven veterinary officers, including two women. The butchers come from various ethnic groups, mainly from southern and northern Chad, but cooperation between them remains strong despite their differences.

An uncertain future?

In this context, the question arises: could these tensions between herders, butchers, and customers become a trigger for conflict in the future? Efforts to maintain peace and collaboration between these actors are essential to ensure the sustainability of this institution, which remains a symbol of coexistence in a country marked by diversity and social challenges.

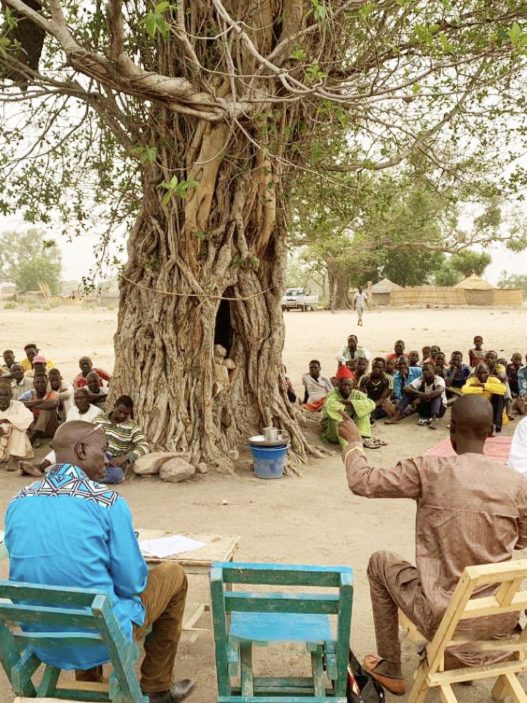

Nomadic pastoralism

This article was written as part of the project “Support for the drafting of reports on nomadic pastoralism by GIZ and Voice4Thought (V4T)” which aims to strengthen social cohesion and reduce polarisation in Chad, particularly in pastoral areas where violence is frequent. For several years, Chad has been marked by recurring conflicts between herders and farmers, which have had a profound impact on the social cohesion of the communities concerned. According to a report by the Crisis Group, between 2021 and 2024, more than 1,230 people were killed and more than 2,200 injured in various agro-pastoral clashes in the south and center of the country[1]. Rural populations are particularly vulnerable to this insecurity. These conflicts often take on an ethnic and religious dimension, exacerbated by political rivalries that fuel community divisions. Social and emotional polarization is very often reinforced by the spread of discourse on social media. Despite measures taken by the government to prevent this violence, the risk of atrocities remains high, threatening the ties between herders and farmers.

The project trains journalists to produce depolarizing stories to counter often sensationalist and inaccurate “bad buzz.” The articles written by participants after their investigations in Mao, N’Djamena, Pala, Chari-Baguirmi, and Doba highlight positive and inclusive alternatives to combat these phenomena.

[1] Crisis Group Africa Briefing No. 199, Nairobi/Brussels, August 23, 2024.