January 25, 2025. A month and a half after the conflict between the sedentary population of Timbéri Township and nomads, we find ourselves in Timbéri, the epicenter of tensions, located 52 km from the city of Goré. At first glance, everything seems calm. Nomads and sedentary people walk side by side on the wide red laterite road that runs through the village. After getting out of our vehicle, we head toward the canton chief’s palace, guided by our country’s tricolor flag. Along the way, we notice locals and outsiders eating lunch in half-closed restaurants. Under a shed, a dozen young men and women are sipping bilibili, a local Chadian drink made from sorghum millet. Their eyes turn towards us. One of them calls out to us: “Is that bread you have in your hands edible?” We answer in the affirmative and approach to give it to him.

After this brief interaction, we continue our way. When we arrive at the chief’s palace, a woman welcomes us. Five minutes later, we explain that we have come to meet the chief. She informs us that he has left for N’Djamena for medical treatment. We ask her if he has a representative there and she kindly takes us to the chief’s secretary. The secretary is listening to the 2 p.m. news on ONAMA Chad radio, sitting under a Nîmes tree in his compound, surrounded by straw.

After a few minutes, we introduce ourselves and present our mission order, briefly explaining the purpose of our visit. The woman who accompanied us is still present. As soon as she hears that we have come to talk about the conflict between herders and farmers, she becomes angry and starts insulting the Mbororo, accusing them of being “heartless people” who “will not see God” because they kill and shed the blood of innocent people without any fear. She then launches into an account of how her field was devastated by cattle in a single night: two hectares of sorghum reduced to nothing. As a widow and mother of two boys she depends on her own resources to provide for them. She concludes bitterly: “Vengeance is God’s, because in this country there is no real justice for the poor.” With these sad words, she leaves us.

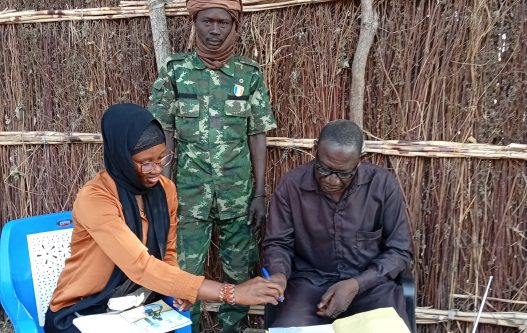

Then we begin our interview with the chief’s secretary, who takes the time to read through and sign our mission statement. When ask about the causes of these recurring conflicts the chief’s representative explains: “It is over the last four years that the conflicts in this area have escalated. Previously, the canton of Timbéri was a haven of peace. Even when nomads arrived from the north with their livestock, tensions remained limited, as their herds did not exceed ten head. But today, the situation has changed. New herders have arrived from Niger, Nigeria, northern Cameroon, and especially in large numbers, with much larger herds. This has changed attitudes.”

He goes on to point out that in the past, a farmer cultivated two to three hectares of land, which is no longer the case today with modernization. Now, eight to ten hectares are needed for a viable farm. The more land farmers occupy, the less they respect the transhumance corridors. On the livestock side, a single herder can own more than fifty head of cattle, which he cannot watch all the time. This failure by farmers to respect transhumance corridors deprives herders of space and passage for their herds. The year 2024 was a tragic year for the canton of Timbéri. Two episodes of this conflict caused numerous human losses and considerable damage, plunging the region into despair.

After our discussion with the chief’s representative, we meet a man who introduces himself as a delegate because of his popularity. In his view, the situation in the village is calm, but everyone remains on guard because tensions could rise at any moment. We sense a spirit of hatred and pain within this community, as well as a lack of compassion for others, due to the deep trauma left by the events they have experienced.

The first incident occurred on Sunday, July 16, 2024. A farmer was weeding his field when a herder passed by with his cattle. The cattle entered the field. The herder, armed with a knife, shot the farmer, wounding him in the thigh, as he simply asked him to remove his animals from his field. Faced with repeated incidents of this kind, the villagers, seeing their brother wounded and taken to hospital, decided to fight back against the herders. This led to the deaths of four farmers and three herders, as well as eight wounded in the space of two days.

When asked about their motives, the herders explained that they were simply demanding space for their livestock, accusing the farmers of occupying all the available land. The farmers responded that the land was communal and that they would not give it up to “newcomers” who were only looking to water their herds. The intervention of security forces from Goré and Doba finally calmed the situation.

On December 8, 2024, a second incident broke out in the village of Koundou, located 5 km from the canton of Timbéri. This conflict left twelve people dead and nine wounded. Grain stocks were reduced to ashes, banknotes were burned, and around 40 houses were set on fire. It all started with the death of an illegal immigrant, who was shot and then cut up. Four days later, around 30 sedentary people gathered to attack the village of Koundou at around 5-6 a.m. It was at this point that the damage mentioned above was observed. The seriously injured were transferred to Goré and Moundou.

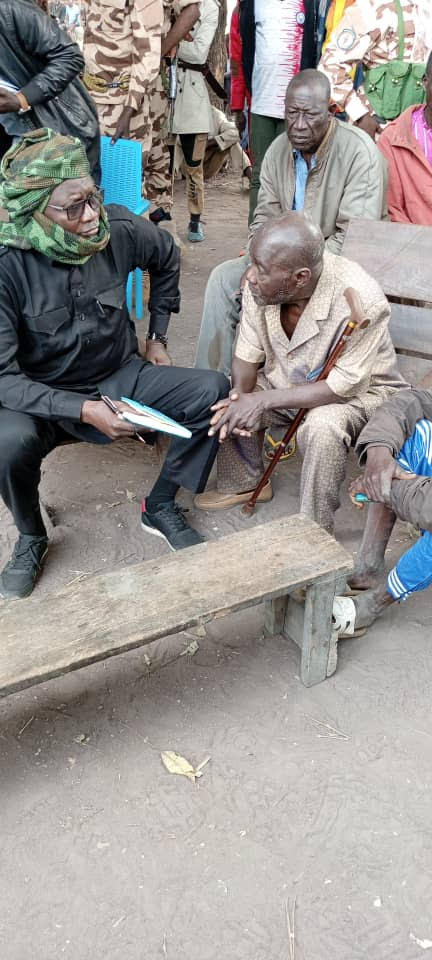

This event attracted the attention of the Chadian government. On the instructions of the president, two ministerial teams were dispatched to the scene: the Minister of State for Territorial Administration and his counterpart for Public Security and Integration, accompanied by a large delegation of law enforcement and security officers. Their mission was to assess the situation on the ground and express their sympathy to the victims. The team was welcomed by the governor of Logone Oriental province for a visit to the scene.

During the visit, a youth representative expressed his dismay in these terms: “Today, if you file a complaint against a herder, you will be dragged through the courts for as long as possible. Dear authorities, there is no greater wealth in the world than living in peace.” Aware of the gravity of the situation, the Minister of State for Territorial Administration took the opportunity to make a solemn appeal to village chiefs and local leaders, urging them to regain control of the situation. “What is the point of state authority if the people take justice into their own hands?” he said.

During the visit, a youth representative expressed his dismay in these terms: “Today, if you file a complaint against a herder, you will be dragged through the courts for as long as possible. Dear authorities, there is no greater wealth in the world than living in peace.” Aware of the gravity of the situation, the Minister of State for Territorial Administration took the opportunity to make a solemn appeal to village chiefs and local leaders, urging them to regain control of the situation. “What is the point of state authority if the people take justice into their own hands?” he said.

Despite awareness campaigns carried out from village to village with the cantonal team, as well as meetings with pastors, imams, and the population, conflicts between herders and farmers continue to escalate. Fear and mistrust persist between nomads and sedentary populations.

Chad is a refuge for many displaced people, many of whom are Fulani herders and farmers, not to mention the Zaraguina (road bandits) and other criminals. Timbéri, located near the border with the Central African Republic, is surrounded by sites sheltering refugees who have lost everything and depend entirely on humanitarian aid from NGOs. However, with the gradual departure of these humanitarian organizations due to the decision of the current US president, these refugees risk being abandoned to their fate. They will then be forced to seek land to cultivate, even though space is already severely lacking.

The situation is increasingly spiraling out of control for the authorities who are struggling to put a definitive end to these conflicts. In addition, the main road through Timbéri to the Central African border is in a deplorable state. Dear readers, imagine what will become of the canton of Timbéri and its surroundings by 2030 if no lasting solution is found.

The names of the authorities are known to the editor