The explosive coexistence between Fulani herders and Noé National Park

In the Mayo-Binder department of Chad, a silent war has been raging for years between Fulani communities and Noé National Park. This biodiversity sanctuary, vital for wildlife, has become the center of a complex conflict between environmental conservation and the survival of local populations.

Binder: a Fulani land in transition

A former Muslim chiefdom founded between the 17th and 19th centuries, Binder is now a canton ruled by a Lamido (Fulani sultan). Its population, mainly Fulani, traditionally lives from agriculture and transhumant livestock farming. The establishment of the national park has disrupted this ancestral balance. “We are caught between a rock and a hard place,” sums up a local dignitary. The park’s water sources and grazing lands, which are essential to wildlife, are also coveted by herders whose herds suffer from recurring diseases linked to overgrazing.

Elephants vs. agriculture: a food crisis looms

Moustapha, a famer in binder, laments: “The elephants destroyed my millet field. I have nothing left to feed my family.” However, his case is not unique:

150,000 CFA francs on average investment is lost per destroyed field, 30 bags of harvest destroyed in one night, and no compensation despite complaints.

“I abandoned my corn field after it was destroyed. As prefect, I don’t even know who to complain to,” says the department administrator, a victim himself.

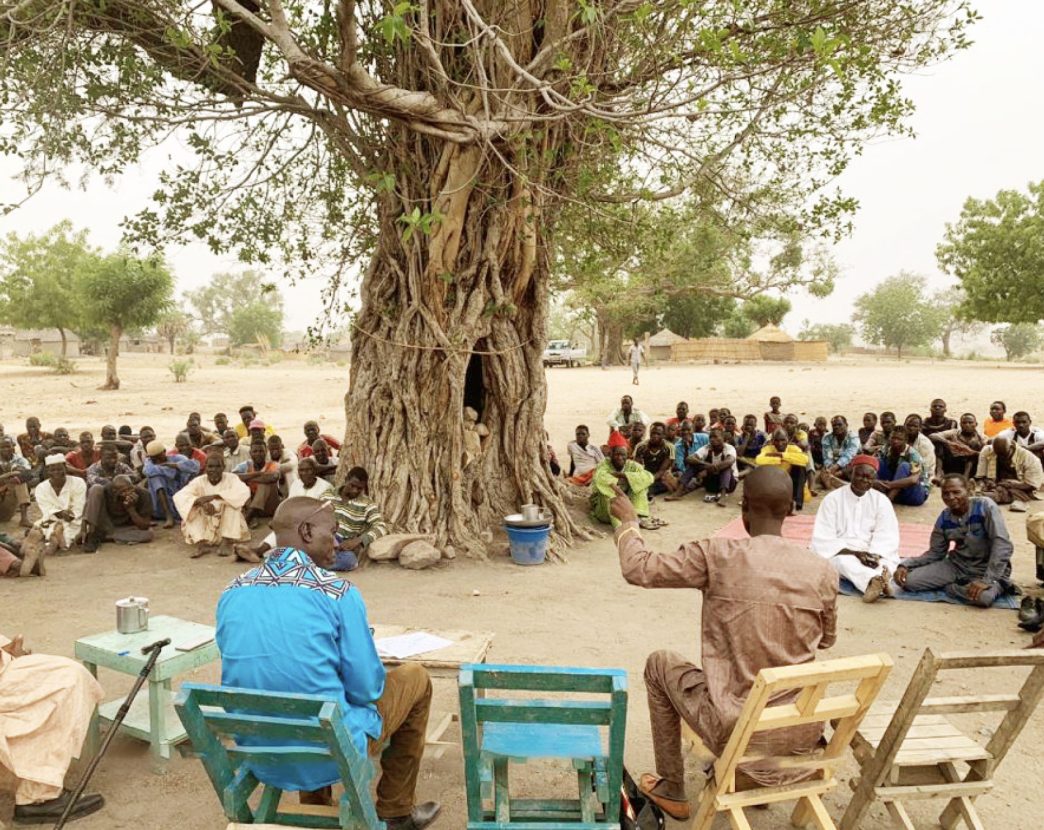

Anger is mounting

In front of the sub-prefecture, the tension is palpable: “We are tired of promises!” exclaims Hamadou. “Every time we file a complaint, nothing changes!”

The NGO Noé, which manages the park, says it is unable to compensate for all the damage. Meanwhile, herders complain of excessive fines (12,500 CFA francs per head of cattle) when they enter the park to look for fodder.

Memory and mobility: the roots of the conflict

Oumarou, 96, recalls: “I saw my first elephant 52 years ago near Kagay. Today, they come into our fields.” This change in animal behavior can be explained by intra-park mobility (search for food/water) and expansion outside the park due to the reduction of their habitat.

Imminent exodus?

Faced with the authorities’ inaction, residents are threatening: “If this continues, we will go to Cameroon.” This is a cry for help that highlights the urgent need to: install electric fences, create transhumance corridors, establish a transparent compensation fund, and involve communities in park management.

It is therefore imperative to find a balance between biodiversity protection and the rights of local populations before this crisis escalates into a humanitarian disaster.

Nomadic pastoralism

This article was written as part of the project “Support for the drafting of reports on nomadic pastoralism by GIZ and Voice4Thought (V4T)”, which aims to strengthen social cohesion and reduce polarisation in Chad, particularly in pastoral areas where violence is frequent.

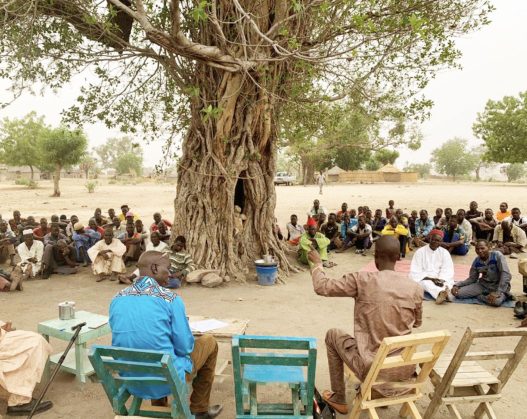

For several years, Chad has been marked by recurring conflicts between herders and farmers, which have had a profound impact on the social cohesion of the communities concerned. According to a report by the Crisis Group, between 2021 and 2024, more than 1,230 people were killed and more than 2,200 injured in various agro-pastoral clashes in the south and center of the country[1]. Rural populations are particularly vulnerable to this insecurity. These conflicts often take on an ethnic and religious dimension, exacerbated by political rivalries that fuel community divisions. Social and emotional polarization is very often reinforced by the spread of discourse on social media. Despite measures taken by the government to prevent this violence, the risk of atrocities remains high, threatening the ties between herders and farmers.

The project trains journalists to produce depolarizing stories to counter often sensationalist and inaccurate “bad buzz.” The articles written by participants after their investigations in Mao, N’Djamena, Pala, Chari-Baguirmi, and Doba highlight positive and inclusive alternatives to combat these phenomena.

[1] Crisis Group Africa Briefing No. 199, Nairobi/Brussels, August 23, 2024.