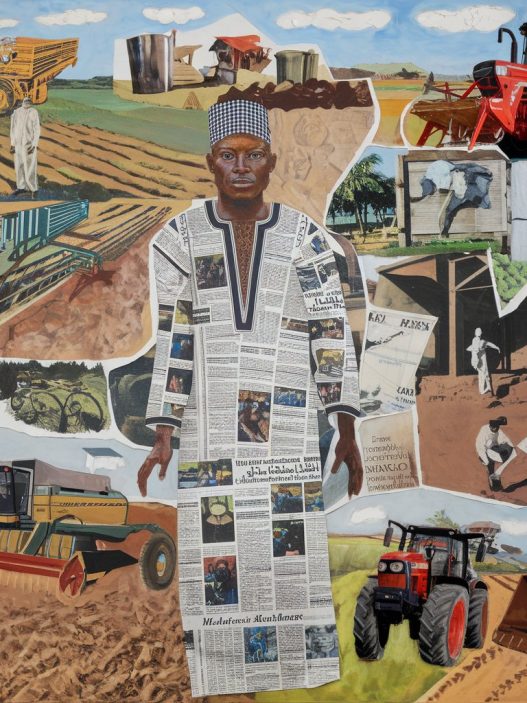

In the floodplains of Koundoul, south of the capital N’Djamena, the fertile soil feeds people, but it also fuels conflict. In recent years, Massa farmers and Arab herders have been fighting over access to a resource that has become scarce: land. However, amid this tension, voices have been raised, and an unexpected dialogue has emerged.

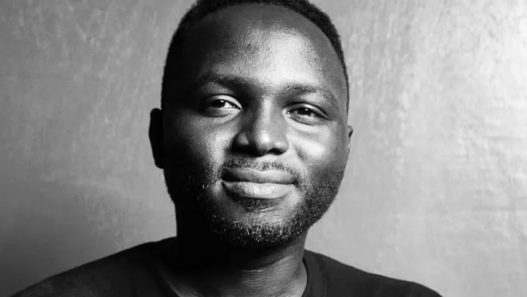

The muezzin’s call has just faded away in the small village of Marmatodji. It is just passed 4 o’clock in the afternoon when Adoum Deye welcomes me in the cool shade of the large Nimier tree, which serves as a reception area for visitors. In the relative silence of the evening, the only sounds to be heard are those of oxen being untied from their posts and the deep voices of young herders calling their flocks.

Adoum Deye, his turban tightly wrapped around his head, leads the way. At 28 he already has two decades of experience as a shepherd behind him. His voice rises in the damp air: ‘Hey… hey… hourtch!’ The oxen mingle, their heavy hooves crushing the ground still wet from the previous day’s rain. Around him, other young Arab herders accompany him. Tonight’s mission is simple: to drive the oxen far away to prevent them from venturing into neighboring gardens. But the apparent simplicity hides a very complex reality. “Today, space is saturated. If you’re not careful, and your cattle slip into a field, the farmer will immediately appear, angry. It ends in a fight,” says Adoum, adjusting his shepherd’s crook.

Like many young Arab herders in the area, he experiences the tension between agriculture, livestock farming and rapid urbanisation daily. Every outing is an uncertain challenge. Between barbed wire fences, rows of mango trees and fields of rice or millet, the herd moves with difficulty, as if in a maze. A single mistake, a single misstep, and the incident can trigger a conflict between the owners of these fields and the shepherds.

To understand this tense climate, we need to go back a few decades. In the 2000s, the Koundoul floodplain resembled a huge playground for young shepherds. Herds roamed freely between the Logone River and the village pastures. After Koranic school, children would run happily behind the herds. Farmers, for their part, planted millet and sorghum in defined areas, leaving large areas for the herds to pass through. “Our parents took the issue of land lightly. We thought it was inexhaustible. Today, everything is sold to city dwellers and there is no more space for grazing,” explains Adoum bitterly.

This phenomenon began to occur in the 2000s and 2010s. With the increasing urbanisation of N’Djamena entire sections of the plain have been divided up and sold off. Local authorities, often complicit, sell land to city dwellers eager for enclosed gardens or building plots. For herders, this is a serious blow. Herds now have to travel miles to find grass. Many families entrust a large part of their animals to Fulani herders, who are responsible for taking them to the areas still available in Mandalia and Lougoun-Gana.

The reduction in grazing land has led to clashes. Adoum recalls a striking scene: “One afternoon a few years ago, a misunderstanding almost ended in tragedy. On the road to Malo-Gaga, a poorly supervised herd invaded a rice field. The farmer, Massa, was alerted and arrived in shock, brandishing a club. He struck the young Fulani shepherd who was guarding the herd. Within minutes,” Adoum continues, “young Arabs rushed in with arrows, machetes and clubs. The Massa also came to reinforce them. We thought blood would be shed.”

However, confrontation was avoided thanks to the intervention of a few elders from both sides. “When people know each other, sometimes a simple word is enough,” says Adoum. But this episode left a lasting impression: the peace that was once natural is no longer guaranteed today.

In the past, solutions to conflicts were found at the Boulama, the respected traditional chief. After assessing the damage, he would impose reparations: the number of plants destroyed, the amount of money to be paid. Today, this authority is neglected here. The younger generations contest his decisions, and appeals are made to the gendarmerie or police stations, which are often corrupt and slow.

Between fields and herds, the Alwida Salam association, young people facing conflict in the plains of Koundoul

In the plains of Koundoul, the future seems bleak due to uncontrolled urbanisation, agro-pastoral and land conflicts, and climate change. It is in this context of tension that a new idea was born. On 13 June 2016, the Alwida Salam association was created, a name that means ‘Union for Peace’ in Arabic. Adoum Deye is its coordinator.

“We said: enough is enough. If we young people don’t get organised, tomorrow there will be nothing left: no pastures, no land, no herds, no peace,” Adoum says.

It is easy to understand why the young people of Alwida Salam are showing another way forward: that of a youth that refuses to suffer and stands up to defend peace. This solidarity initiative strengthens social cohesion by joining other associations in the municipality of Koundoul. “Our association is affiliated with the Coordination of Youth Associations for the Development of the Sub-Prefecture of Koundoul (CAJDSK). This platform brings together all the diverse youth organisations in the area. Farmers, fishermen, herders, traders, students, come together. It is a real framework for mixing and cohabitation, where each young person who is part of it acts as a relay for their community,” says Adoum.

The real motivations behind the creation of Alwida Salam

Contrary to popular belief, it was not simply a desire to help each other that prompted these young people to come together. Their motivations are deep and varied. First, uncontrolled urbanisation: the expansion of the city of N’Djamena is absorbing the plains without any planning, pushing herders further away. Second, economic survival: protecting livestock means protecting their future. Another motivation is the loss of traditional authority: the boulama chief no longer has the same regulatory power and conflicts are being resolved violently. Lastly, peaceful coexistence: establishing an inclusive framework for dialogue where every member’s voice counts.

“We realised that we needed to organise ourselves,” explains Adoum. “Alone, each of us is weak. Together, we can defend our rights peacefully and prepare for a better future.”

Alwida Salam is not just a local association, it is a state of mind. Young people refuse to allow coexistence between farmers and herders to be disrupted by land issues and the lack of regulation. By increasing solidarity actions and cultivating dialogue with neighbouring farmers, they are showing that another way is possible.

Alwida Slam’s first action was simple but fundamental. Each member contributes 500 CFA francs per month to the fund. After a while, the association used this fund to purchase collective goods: fifty mats, two hundred glasses, five tents, thermos flasks and coolers. These goods are used for weddings, funerals and other ceremonies. “Even the Massa and other communities come to borrow them. When your neighbor uses your mat for his wedding, he sees you as his brother, not his enemy,” Adoum points out.

Gradually, the association has established itself as a key player in the village. The elders themselves come to consult the members in the event of a dispute. Thanks to their education, some young people know how to navigate between custom and administration: they help draft complaints and refer cases to the courts.

In the plains of Koundoul, the agro-pastoral conflict is not just a simple clash of interests: it reflects the major challenges facing contemporary Chad. Uncontrolled urbanisation, land sales and the effects of climate change offer an uncertain future.

In this troubled landscape, the challenges facing Alwida-Salam extend far beyond the village of Marmatodji. Climate change is reducing the availability of grazing land. Population pressure is increasing competition for land. Uncontrolled urbanisation is transforming floodplains into residential areas. These young Arab herders are aware of this: “If nothing is done, tomorrow there will be no more room. Neither for fields nor for herds,” he concludes. Faced with these challenges, Alwida Salam does not offer a miracle solution. But she does propose a way forward: that of dialogue, solidarity and youth responsibility.

In the shared laughter during a ceremony, in the handshake between a herder and a farmer, in the meetings at the Koundoul community library, there is a glimmer of hope: that young people, by refusing to accept conflict as inevitable, can pave the way for harmony.