In the canton of Mango in southern Chad a major crisis has developed around transhumance corridors, highlighting deep tensions between herders and farmers. As the need for a fair and meaningful resolution to the conflicts becomes increasingly urgent, the question arises: does justice lie in the official courts or in community mediation?

On July 21, 2025, as the sun reached its zenith, I made my way to the village of Mango, located north of the cantons of Koutoutou and Kara, southeast of the cantons of Béti and Bédjiondo, west of the cantons of Nankessé and Nassian, and northwest of the village of Sama. At the ‘Crossroads of Coexistence’ I meet with members of the community.

The village of Mango has existed for two centuries as a collective society. It is made up of several neighborhoods where Gouleyes, Ngambayes, Nangtchérés, Arabs, and Mangos live. Livestock farming and agriculture are the main economic activities. Transhumance corridors, specific routes used by herders to move their livestock between seasonal grazing areas are crucial to ensuring coexistence between herders and farmers. However, due to climate change and population growth, these corridors have become less accessible and reliable than before.

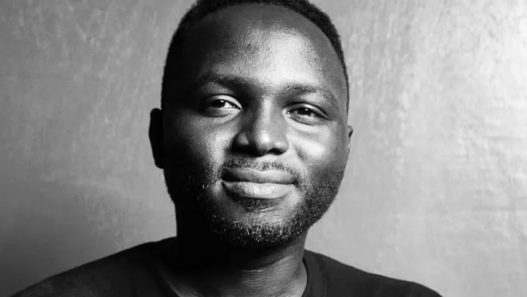

At the entrance to the village, I meet a group of herders and farmers exchanging greetings. After the customary greetings, “lapia” and the “salamalek”, I meet Adam, a herder dressed in a large colorful boubou, who raises his livestock in the neighborhood Koubou, and Peurhongar, a farmer wearing a colorful shirt and a traditional hand-woven raffia hat. The two have found themselves increasingly at odds because Adam is fighting to protect the paths that guarantee access to water and pasture for his herds, while Peurhongar needs the same land to feed his family. Over time the situation became a source of conflict, as every time a cow ventured onto cultivated land, it led to confrontations. The farmers’ frustration grew, and they did not hesitate to voice their discontent. Insults flew during village meetings on all sides, creating an already tense atmosphere.

One day, during a meeting in the royal courtyard of the chief of the land Ngarbe, the situation erupted. The villagers gathered under a large mango tree, the usual place for discussing community issues. Voices were raised, and tensions were high. According to my informants, Mr. Peurhongar, agitated, addressed Adam and the other herders in these terms: “You have always ignored the fact that these lands are essential for feeding our children and our families.” Peurhongar raised his voice with great anger and despair toward the herders.

Feeling betrayed by Peurhongar, Adam replied forcefully: “Don’t you think that without our herds, your future is in danger and at risk?” The murmurs of approval from some and the grunts of discontent from others amplified the emotional and aesthetic atmosphere. The looks were full of resentment and everyone stood their ground, closing the door to any constructive dialogue. This moment of tension, where anger and frustration mingled, marked the beginning of an escalation of violence that would tear the community apart. Verbal quarrels quickly turned into acts of sabotage and aggression, foreshadowing dark days ahead for the village of Mango.

A tragic night

These incidents led to acts of violence. During a tragic night, a clash broke out between the two sides. The angry herders attacked a field of peanuts and cotton, while the farmers, armed with sticks, slingshots, and machetes, defended themselves. The result was devastating: a young farmer named Yoram lost his life in the clash, and his death plunged the community into shock and confusion.

The police were called by the land chief to restore order, but tensions were already running high. The toll was as follows: 65 arrests, including 45 men and women. Several knives and firearms were seized from the protagonists. Seventeen herds were burned, and 345 hectares of fields – cotton, peanuts, ceramics, rice, corn, squash, and tubers – were destroyed. More than 300 huts were burned down and a total of eight hundred and 855.000.000 CFA francs went up in smoke.

The Secretary General of the canton informed us that after the violent clashes between the two groups, the situation became untenable throughout the village, with killings and waves of emotional violence against the elderly and sexual violence against minors on both sides. According to him, the traditional authorities are unable to contain the conflict.

In the aftermath of the conflict, the intelligence police conducted a thorough investigation in the village of Mango and the surrounding area, gathering anonymous testimonies and material evidence. This led to the arrest of members of both groups who had fled and the suspects were taken into custody. Meanwhile, the police are continuing their investigation, questioning suspects and gathering additional information. Each suspect was given the right to legal representation. After a period in custody, investigators compiled a file containing witness statements, material evidence, and statements from the victims.

The process

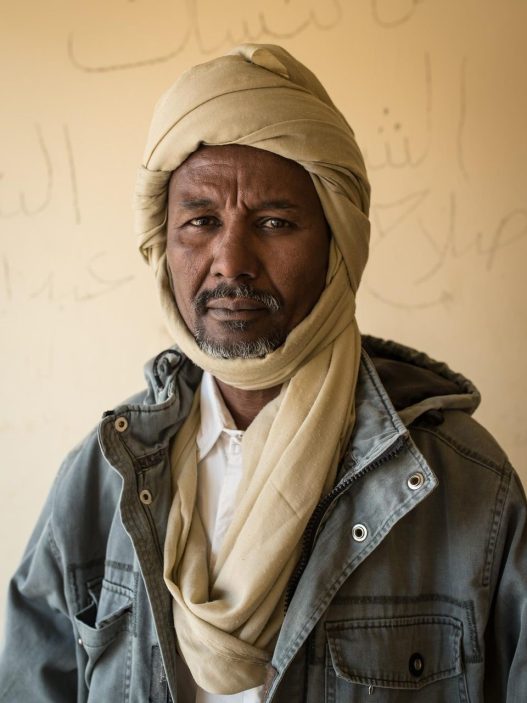

The following day, public questioning began at the Doba Police Station. Taking the floor, Commissioner Oïtana greeted the audience and called on both sides to show strict respect before God and the law. The floor was then given to the village chief and other notables, who stated that the problem of managing transhumance corridors was not a new one: “It is a conflict that has been perpetuated and fueled by the administrative and military authorities, who have no capacity for peaceful conflict management or local governance.” They added that most of these administrators are illiterate and poorly equipped with knowledge of land laws. The floor was then given to the herders to present their version of events. The representative of the herders began his comments with disrespectful movements and gestures, pointing the finger at the incumbent commissioner, Oïtana, and placing the responsibility for the conflict on the state apparatus, which is supposed to enforce the laws governing transhumance corridors.

According to the laws of the Republic, disturbing public order and disrespecting judges are punishable as follows: in the event of disruption of the hearing, interruption of the judges, or other behavior that interferes with the proper conduct of the trial, penalties may be imposed. These can range from a simple warning to a fine or even imprisonment. Any disrespect towards judges may result in penalties. Judges are representatives of the judicial authority and must be treated with respect. Thus, the commander of the urban police, Mr. Djasrabé, ordered the prison guard, Mr. Seid, to impose a prison sentence on Adam for disrupting the hearing. The commander then suspended the trial for a good 30 minutes to allow calm to be restored.

After resuming the trial and releasing Mr. Adam, the police commander gave the floor to the farmers’ representative for their closing arguments. The representative of the herders verbally attacked Adam for being at the center of this conflict, which had brought grief to the farming community for the benefit of the herders. Given the climate and mistrust between the two sides, Deputy Police Commissioner Abakar suggested that Chief Commissioner Djasrabé refer the case to the higher courts (the Court of First Instance).

No sooner said than done, the chief commissioner and the urban police commander decided to refer the suspects to the High Court in Doba. A week later, the trial began with a hearing at which the prosecution and defense teams presented their arguments. The victims and witnesses were also called to testify. After hearing both sides, the court deliberated to determine the guilt or innocence of the suspects.

What happened next

Three days later, the verdict was announced after a period of deliberation. If the suspects were found guilty, the judge handed down sentences ranging from simple fines to prison terms. During the meeting, participants shared their stories and ancestral experiences. This process not only brought the acts of violence to light but also revealed underlying tensions in the community.

The bereaved families of the young farmer felt the pain not only of losing a loved one, but also of the growing divide between them. The following days were marked by an atmosphere of mistrust and fear. The herders barricaded themselves in their homes, fearing reprisals, while the farmers, supported by sympathizers from other parts of the region, intensified their demands. Stereotypes hardened: herders were seen as intruders, while farmers were perceived as opportunists. The once-united community was now divided, with each side digging in its heels.

According to my sources, those involved felt that the trial over the transhumance corridor in the village of Mango had not been conducted fairly. According to Mr. Goladoum, secretary of the Mango farmers’ associations, the farmers were sentenced in absentia to pay a fine of 500,000 CFA francs to the herders for destroying their animals and damaging their homes. He added that it was their fellow farmers who suffered heavy losses, losing one of their youngest members, Titingar, during the conflict. One of them, who requested anonymity, even stated that the Chadian justice system is not fair, claiming that it favors a clan, families, and a community that support each other.

Amidst this chaos, Tamadjal, approximately 86 years old, the first female teacher in the village and president of women’s organizations and associations fighting poverty and promoting the well-being of the village community in Mango, began to think about solutions. She has always dreamed of a future where herders and farmers can coexist. According to Ngatabe, representative of the village elders of Mango, Tamadja is a force for cohesion and peace in the village. The pain in the eyes of the families affected by the violence prompted this woman to act. Tamadjal began organizing discreet meetings between a few members of the two groups, seeking to establish a dialogue. She invited Adam and Peurhongar to participate, but at first, they were reluctant, distrustful of each other. However, a chance encounter changed everything. During a village meeting organized by the Justice and Peace Commission (CJP), of which Tamadjal is the focal point, Adam, Peurhongar, and the elderly woman Tamadhal found themselves face to face. The elderly Tamadjal woman took advantage of this meeting to speak, sharing her dream of peaceful coexistence. She recalled memories of a time when herders and farmers shared resources and children played together in the fields. “We all need this land,” she pleaded, “but we can find a way to share it,” so that each group could feel comfortable and go about their business. These powerful testimonies, linked together by Tamadjal, began to bear fruit on both sides. The two camps began to listen more to this woman’s commitments and words, finally burying the hatchet. Tensions began to dissipate. Adam, touched by her commitment, and both sides, along with Tamadjal, began to reconsider their positions.

They agreed to participate in another community forum called “Djiraybé Altadoum”, which literally means “let’s build the city through work”, bringing together often ignored voices, the “silent ones” who long for peace. Peurhongar, also influenced by Tamadjal’s appeal, agreed to engage in dialogue, recognizing that a peaceful solution was necessary for the future of their families. The forum was a turning point. Poignant testimonies were shared, stories of suffering and loss, but also visions of hope. Participants agreed to establish rules for sharing resources, set up land rotation systems, and create joint committees to resolve future conflicts.

People need land for several essential reasons. First, it is a source of life, providing resources such as food, water, and materials to build shelters. For farmers and herders, land is also a vital space for growing crops and grazing their animals, which is crucial for their economic survival.

What is the role of mediation?

Mediation in land-related conflicts is important because it allows parties to find peaceful solutions without resorting to violence. This approach promotes dialogue and helps build trust between different communities. People appreciate this form of mediation because it gives them the opportunity to actively participate in resolving conflicts, rather than leaving decisions in the hands of outside authorities. Aspects that work well in this type of mediation include listening to and respecting the needs of each party. By involving both sides in the discussion, compromises can often be found that satisfy everyone’s interests. In addition, mediation helps preserve social ties and community cohesion, which are essential for long-term stability. Thanks to empathy and mutual understanding, tensions began to ease. Mango’s story illustrates that even in the worst moments of polarization, dialogue can open paths to reconciliation. Conflicts can arise between herders and farmers, but solutions are possible, as illustrated by the case of this Tamadjal woman. Adam Peurhongar, while still aware of the challenges ahead, is committed to working together to build a better future. Tamadjal, as a catalyst for this change, continues to play a key role, proving that the will for peace can overcome historical divisions.